I’m a big fan of this old-school (1972) anime called Gatchaman (and of its American translations…well, some more than others). Author and friend Jason Hofius wrote a definitive guidebook on one of the American translations, which was called Battle of the Planets (1978), and recently he sent me an email to tell me he’s created a website on the same topic.

So I went tooling around the website, and it struck me that writers could learn a few things from his approach to the information.

Story Conflict

In the Battle of the Planets series, as in most stories, there are bad guys and there are good guys. The bad guys are from the planet Spectra. Because Spectra is dying, the bad guys run around consuming the resources from the Peaceful Planets and generally trying to destroy the Peaceful Planets using monster mecha machines. The good guys belong to the Intergalactic Federation of Peaceful Planets, which is a very green and scientific sort of group. The Federation’s most important answer to attacks from Spectra is the 5-person G-Force ninja team. (Please rest assured that this came long before Disney’s elite guinea pig team. The members of this G-Force are human.)

Here’s what struck me, though. For each and every one of the series’ 85 episodes, Hofius indicates what Spectra is trying to accomplish and what the G-Force team is trying to accomplish. You might think this would get ridiculously redundant (for example, Spectra’s Goal: To steal a precious mineral; G-Force’s Goal: To stop the Mecha of the Week and recover the stolen mineral) but it really doesn’t because each side has numerous sub-agendas and internal conflicts (read: subplots).

Your Writing

You may know who your good guys and bad guys are overall, and what each side’s mission is in your story or novel as a whole, but do you know what the key conflict is in each scene? If your story is moving forward properly, each scene’s conflict should be a little different as the characters react and respond to each other. Each scene’s conflict should also advance the story as a whole.

As I edit a novel, I often find that I have several redundant scenes, usually because I am trying to make a point of some kind. But a story is more exciting (and fun) if it doesn’t get mired in redundancies.

For example, in the novel I’m currently working on, I found three scenes meant to emphasize how bad things were for the good guys now that the bad guys had successfully invaded—the good guys had reached the point of surrendering not just physically, but also psychologically.

For example, in the novel I’m currently working on, I found three scenes meant to emphasize how bad things were for the good guys now that the bad guys had successfully invaded—the good guys had reached the point of surrendering not just physically, but also psychologically.

My goal was to prove that things were BAD, and I did such a good job with it that I found myself depressed and a little hopeless, even though I knew the good guys would eventually prevail. There’s nothing pretty about beating a dead horse, folks, and if you insist on doing so, your readers may beat a hasty retreat.

Though I’m not much of a chess player, the craftiness of the game has always intrigued me, and so I like to think of a story like an intense chess game between sides. One side moves; the other side has to counter that move and not only block the opponent’s goals, but also further its own.

So take another look at that story you think you’ve finished. Is it as tight as it can be? Do the conflicts between characters evolve and change with each and every scene? If not, can you combine scenes or otherwise hone things down to keep your writing razor edged?

Character Guides

Back for a moment to Hofius’s website. In addition to the great episode guides, he provides fantastic character guides. Again, what strikes me about them is that they’re different from every other character guide I’ve ever seen for the series (and I’ve seen a bunch and even written a number of them).

Rather than focusing on the obvious—G-Force team member Mark, for example, has blue eyes and likes airplanes—Hofius tells us about the characters, referencing at least one episode for each tidbit. That “at least one episode” is important—the show’s creators were fairly consistent in developing the characters’ abilities.

Your Writing

You may have character sheets, but have you managed to work details that define your characters into the story?

I recently did some editing work for an aspiring novelist who’s still mastering the art of working the details into the story. She knew a lot of important things about her main characters, for example, and she did a fantastic job of describing them, but she needed to work on slipping the information in without infodumps or blatant telling (e.g. “I am an honest sort of guy”).

One of the biggest dangers of telling (rather than showing) characterization is that your character won’t ring true to readers. Think about it – if someone you worked with ran around telling everyone what an honorable guy he is, but you never saw him do a single honorable thing, you’d think he was a liar, wouldn’t you? Readers will feel the same way about characters unless they get to see that honor in action.

Your turn: Is your writing as tight as it should be? Are you effectively showing conflict and characterization?

Your turn: Is your writing as tight as it should be? Are you effectively showing conflict and characterization?

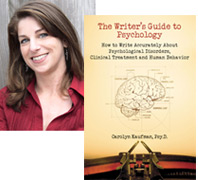

Carolyn Kaufman, PsyD's book, THE WRITER'S GUIDE TO PSYCHOLOGY: How to Write Accurately About Psychological Disorders, Clinical Treatment, and Human Behavior helps writers avoid common misconceptions and inaccuracies and "get the psych right" in their stories. You can learn more about The Writer's Guide to Psychology, check out Dr. K's blog on Psychology Today, or follow her on Facebook or Google+! (Her Gatchman site, which she linked to shamelessly in the post above, is here.)

Carolyn Kaufman, PsyD's book, THE WRITER'S GUIDE TO PSYCHOLOGY: How to Write Accurately About Psychological Disorders, Clinical Treatment, and Human Behavior helps writers avoid common misconceptions and inaccuracies and "get the psych right" in their stories. You can learn more about The Writer's Guide to Psychology, check out Dr. K's blog on Psychology Today, or follow her on Facebook or Google+! (Her Gatchman site, which she linked to shamelessly in the post above, is here.)

5 comments:

I outline my books using Book in a Month by Victoria Schmidt. On her scene cards, there's space for the obvious things like setting and characters, but she also asks for the scene objective. Why is this scene in the book? The answer always boils down to conflict. Either the scene should illuminate the villain's goals to a greater degree, or it should show more of the hero's.

Great post, Julie. Thanks!

I like your insight -- every scene has a conflict that pushes the story along. I'd never thought of it that way, but it makes sense.

A woman of my own heart. I love "Battle of the Planets". It is why I am a writer. Thanks for the book and website link. I am in heaven.

Michelle

But I AM an incredibly honest sort of guy. *Honest*.

I like scenes without conflict interspersed with scenes that have conflict. That way there's a breather for everyone and more exposition.

Post a Comment